Tap Dancing: When Movement Became Music

Tap dancing isn’t just movement. It’s music. It’s rhythm. It’s resistance. It’s identity.

And it stands as one of the most powerful examples of cultural fusion in dance history. Born in hardship, evolved through innovation, and carried forward through generations, tap is a uniquely American art form that speaks with the feet but echoes from the soul.

The Origin of Tap: A Fusion of Cultures

Tap dancing began in the United States during the early 1800s, but its origins trace back across continents, cultures, and centuries. It emerged as a result of `the fusion of:

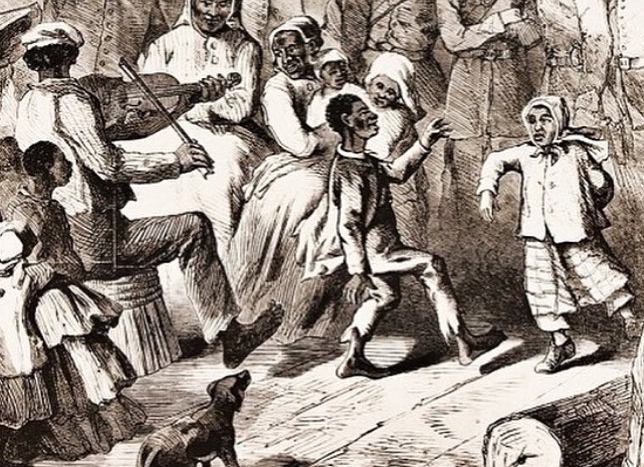

As enslaved Africans were brought to America, and as poor Irish and English immigrants arrived, their traditions collided. Sometimes by proximity, sometimes by necessity. The shared spaces of urban centers became melting pots of rhythm and movement. Over time, these different traditions evolved into something new. Something loud. Something powerful. Something called tap.

But before dancers wore shoes with metal plates, they used the most powerful instrument they had: their bodies.

1730s–1740s: Drums Banned in the American South

Why?

Drums were more than music. They were a means of communication across plantations, and authorities feared they could be used to organize rebellions. Silencing the drum was a way to try and control the people.

But rhythm would not be silenced.

Mid-1700s: The Rise of Body Percussion

Deprived of drums, enslaved Africans turned to their bodies. They created complex, layered rhythms through “patting juba” — a rich and expressive form of body percussion that included:

Hand clapping (often syncopated and offbeat)

Thigh slapping and chest patting

Foot stomps and heel drops

Finger snaps and other percussive sounds

These rhythms were deeply rooted in African polyrhythmic traditions. Often paired with call-and-response singing, patting juba allowed enslaved people to preserve culture, foster community, and create music even in silence.

What Was Patting Juba?

In West and Central Africa, music and dance were inseparable. Drums didn’t just keep time; they spoke in patterns, carrying messages. When this expression was banned in the U.S., enslaved Africans preserved it by turning their own bodies into instruments.

Patting juba used coordinated body movements to build complex rhythmic structures:

This body percussion became the backbeat of survival, providing music for:

Patting juba was more than just music. It was:

These percussive rhythms laid the foundation for African American vernacular dance, particularly in:

Patting juba would go on to influence the development of tap, particularly when African and European traditions began to meet in American cities.

Late 1700s–Early 1800s: Cultural Fusion in Urban Centers

As African Americans, Irish, and English immigrants lived in close quarters in cities like New York’s Five Points, a cultural exchange occurred.

Irish jigs and English clogs emphasized fast, repetitive steps

African body percussion emphasized rhythm, syncopation, and grounded movement

This accidental collaboration in back alleys, boarding houses, and street corners led to the earliest forms of “tap-like” percussive dancing. Dancers used hard-soled shoes or nailed-on taps to amplify their rhythmic footwork.

These styles would later be co-opted by minstrel shows, often in racist blackface performances. However, the core movements were born of authentic African American and immigrant working-class dance exchanges.

1820s–1840s: Early Tap Dances Appear

This era saw the rise of percussive dance steps that would eventually evolve into tap. Performers in informal gatherings and on stage used:

Shoes with nailed metal soles

Emphasis on syncopated beats and foot-generated rhythms

These elements gained popularity in vaudeville and minstrel circuits, even as the origins remained deeply rooted in African American communities.

Master Juba: Bridging Traditions

This era saw the rise of percussive dance steps that would eventually evolve into tap. Performers in informal gatherings and on stage used:

Shoes with nailed metal soles

Emphasis on syncopated beats and foot-generated rhythms

These elements gained popularity in vaudeville and minstrel circuits, even as the origins remained deeply rooted in African American communities.

1900s–1930s: Tap Dance Formalized

By the turn of the century, tap dancing was entering theaters, clubs, and movies:

Tap became a respected art form thanks to the work of many Black performers who brought sophistication, improvisation, and soul to the form.

Enter the Legends: Bojangles & Beyond

One name rises above: Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Known for his effortless style and groundbreaking routines, he famously tap-danced up and down stairs, and became one of the first Black entertainers to cross into mainstream media.

Robinson’s legacy inspired a new wave of tap legends, including:

Tap had gone mainstream. But it never lost its soul.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson

He wasn’t just a performer. He was a pioneer.

Smooth. Effortless. He famously danced up stairs, becoming one of the first Black tap dancers to break the racial barriers of Hollywood and stage.

Then came Fred Astaire, who brought tap into the Golden Age of cinema. One of his most iconic scenes? Tap dancing with his own shadow in a dreamy black-and-white film.

Tap had gone mainstream — but it never lost its soul.

What Makes That Iconic Sound?

Tap dancers wear special shoes fitted with metal plates on the toe and heel. Every contact with the floor creates a distinct percussive sound.

Tap is the only dance form where the performer creates live music with their body while dancing.

Tap Today: Still Alive, Still Loud

Tap has evolved. Modern dancers mix tap with:

Contemporary tap dancers engage in freestyle battles, experiment with new surfaces and sounds, and keep the tradition both grounded and futuristic.

Modern tap has evolved. You’ll find dancers freestyling in tap battles, experimenting with hip-hop, jazz, funk, and even silence. It’s become a hybrid of storytelling and musicality, passed down from one generation to the next.

And yes — there’s even a National Tap Dance Day in the U.S.

May 25, in honor of Bojangles’ birthday.

Tap dancing may have started in hardship, but today it lives in celebration, passion, and power.

Tap isn’t just about shoes hitting the floor.

It’s about expression, identity, and legacy.

A living rhythm — created by those who refused to be silenced.

So next time you hear that click or tap, remember:

You’re not just hearing dance…

You’re hearing history.

-

-

-

-

-

Dance Studio Software Comparison: DSM vs StudioBookings

LEGEND: = fully supported = limited = not a core feature Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-